Happy Thursday, and welcome to the penultimate edition of Reparations Daily (ish)!

Since today’s edition will link to various New York Times pieces, I won’t be including the usual collection of clips.

I did a mini-analysis of the New York Times coverage on reparations this year for today's Hot Takes section.

Inspired by the Race Forward report, ‘Moving the Race Conversation Forward,’ from 2014 identified key ways in which mainstream media coverage and discussions of race and racism stifled our progress toward racial justice. It found that the bulk of mainstream media’s race and racism coverage concentrated on individual levels of racism rather than structural racism. Their research team examined over 1,000 articles and transcripts from national and local newspapers and cable news transcripts from January-August 2013 and coded each piece for various data points.

I was curious how various outlets covered the issue of reparations in 2021 and initially set out to analyze articles from the New York Times, Washington Post, and USA Today.

However, I quickly realized that would be a weeks-long endeavor, so I pivoted to just focusing on the New York Times. Though, I hope to dig into the other two outlets, particularly the coverage from USA Today since they devoted a 6-month long project to reparations. So, if you have any thoughts or feedback on this mini analysis, please let me know!

Here’s the breakdown of the methodology:

Time Period: Jan 1, 2021-Dec 28, 2021

Number of Articles Reviewed: 30

Publication: New York Times

Variables: Headline, Focus (Local/National), Narrative, Mentions Cash Payments, Mentions Other Types of Payments, Mentions George Floyd, Mention Descendants of Enslaved People, Use of ‘Slave’ or ‘Enslaved,’ Mentions Evanston, Mentions H.R. 40, Mentions the Racial Wealth Gap.

Despite this newsletter including news on reparations worldwide, I decided early into this analysis not to include international-focused articles or articles on Native Americans (though there weren’t many at all) or reparations framed in an incorrect context. While I think these topics are important, I chose to focus this analysis on US-focused news related to reparations for Black Americans.

This analysis is imperfect. Some articles briefly mentioned reparations that I felt didn’t meet the threshold for the data set. Other articles didn’t mention reparations at all. For instance, this article from January on a lawsuit against an Oregon Covid-19 relief fund that was solely for Black residents that I felt should be included. There were reviews of books, like How the Word is Passed or Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?, that I strongly considered including but ended up excluding. But, I hope this mini analysis gives you some insight into how one of the most prominent news outlets covered this issue this year.

Before we get to some of the key findings, here are some helpful definitions for some terms you’ll see throughout this edition:

Frame: A lens applied to a story to promote a particular problem, solution, or moral evaluation in a specific way.

Narrative: A collection of stories we tell each other, rooted in shared values and common themes that uphold a particular frame or worldview.

Framing Effects: Occurs when a person’s judgment about different options is affected by whether they are framed as resulting in gains or losses. (In general, people feel more positive about options framed from a positive viewpoint instead of a negative viewpoint).

Some of the key findings from this quick dive include:

Finding 1: The majority of coverage focused on local reparations efforts

Finding 2: The story of local reparations in Evanston, IL., and the murder of George Floyd was often used as a frame for the NYT’s reparations coverage.

Finding 3: Most articles mentioned cash payments but not H.R. 40.

Finding 4: The NYT often usually uses “slaves,” and “enslaved,” or just “enslaved,” in its articles.

With radical love,

Trevor

Hot Takes

Finding 1: The majority of coverage was focused on local reparations efforts.

With Congress not making any significant moves on H.R. 40 other than the hearing at the beginning of the year, the big win for the Bruce family, the movement on the California Reparations Taskforce, the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre, and the action taken in Evanston, it’s no surprise that most of the NYT’s coverage this year was focused at the local level.

As such, the debate on whether local reparations should be considered reparations also saw increased attention.

Funnily enough, much of it took place in the Washington Post.

In March, Kirsten Mullen and Dr. William Darity (featured in Vol.31) penned an op-ed saying that what’s happening in Evanston isn’t reparations.

Shortly after, Dr. Andre Perry (featured in Vol. 23) and Dr. Rashawn Ray of the Brookings Institute responded with another Washington Post op-ed saying that Evanston’s grants to homeowners weren’t “perfect or final,” but just the beginning.

Then, later in the summer, Robin Rue Simmons, former Evanston alderwoman and founder of First Repair, wrote a piece in the Washington Post, making the argument that we cannot wait for Congress or the White House because “actual reparations, not just their study, can be enacted by cities nationwide.”

With all of the new reparations initiatives that cropped up in 2021, I expect increased local-focused coverage in 2022.

There were only a couple of NYT articles focused on reparations at the individual (person or family) or institutional level (university, seminary, etc.). However, as more funding flows to universities to conduct slavery/reparations-related research, I expect this type of coverage to increase in the coming year.

Finding 2: The story of local reparations in Evanston, IL., and the murder of George Floyd was often used as a frame for the NYT’s reparations coverage.

With Evanston being labeled the “first U.S. city to make reparations” to address historic racism and discrimination, it was often used as a frame in other stories to provide further context on the issue.

For example, an article from April contrasted H.R. 40 with the program in Evanston, stating that “any national program would be much larger” than the $10 million housing grants slated for Black residents in Evanston. Another article focused on the Virginia Theological Seminary brought up Evanston when discussing whether or not to pay cash.

If you read any article on race this year, particularly at the start of the year, you probably heard some assortment of the phrase, “the combination of the Covid-19 pandemic and the murder of George Floyd, laid bare the racial inequities and systemic racism….”

These articles were no different, with 35 percent mentioning George Floyd somehow.

Given the global eruption that followed the video of Derek Chauvin killing Floyd back in 2020, it makes sense that it is still being used to frame other racial justice issues, such as reparations.

My problem is that The New York Times (and the media broadly) has overemphasized the link between Floyd’s murder and the “reckoning” that supposedly ensued. So while we could all see and feel the difference in the reaction to Floyd’s murder, the dust has settled, and the data shows that we haven’t grappled with the issue of race as much as the media says we have.

A poll from just last week found that support for Black Lives Matter dropped 11 percentage points since June 2020.

Do you remember all those pledges and promises from corporations to fund the racial justice movement? According to a Washington Post analysis from August, almost $50 billion was pledged, and only $1.7 billion had made it out the door.

Oh, and remember all of the elected officials who said they would seriously consider scaling down police operations and redirecting funds to things like housing, education, and mental health resources? Yet, a CityLab analysis found that law enforcement spending as a share of general expenditures rose last year.

While I understand the convenience of using Floyd and the phrase “racial reckoning” as a backdrop for these articles, it’s a bit lazy.

Finding 3: Cash payments were mentioned in most articles, and H.R. 40 was not.

The conversation on reparations for Black Americans usually veers in two ways; discussions about who should receive reparations or what form they should take. So, it is no surprise that most of the articles analyzed dove into one or both of the topics.

Of the articles analyzed, 59 percent mention cash payments. There were articles which used a negative frame, like this article which covered an anniversary event to commemorate the Tulsa Massacre. It quotes George Bynum IV, the mayor of Tulsa, who said that “cash payments to survivors would divide the city.”

Other pieces, such as this op-ed from Dr. Darity, discuss eliminating the black-white wealth gap as a core component of a reparations program that would cost anywhere between $54,700 a person to $280,300 a person.

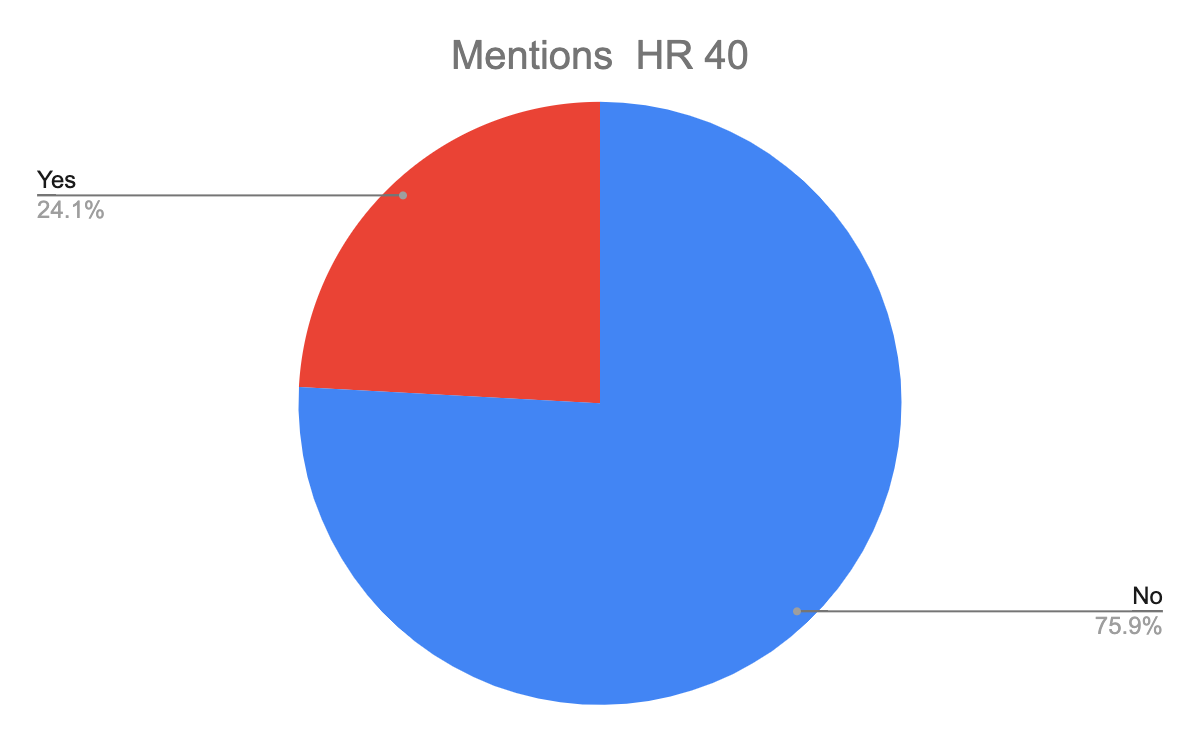

Surprisingly, H.R. 40 was not mentioned in most of the articles analyzed, with only about a quarter of the articles analyzed citing the bill, which advanced out of the House Judiciary Committee for the first time and has the most co-sponsors it’s ever had.

In the articles that did mention H.R. 40, the bill was the article's primary focus.

I think there are a couple of reasons why this is the case, and I’ll divide the blame equally between those in Congress and the reporters who covered this issue.

To me, those in Congress could and should be bringing up H.R. 40 much more often — on social media, in interviews, in private conversations, etc.… But, unfortunately, it is usually a footnote in racial justice conversations; it has been left out of locally-focused reparations news, despite the two being inextricably linked.

Despite this, it’s the journalist's job to dig deep into a story and provide all relevant context on an issue.

A lot of the questions states and localities are grappling with would, in theory, be answered through a federal commission seeking to understand what reparations should look like across the country. So next year, when you see reparations-related news that doesn’t mention H.R. 40, reach out to the reporter and ask why.

Finding 4: The NYT usually uses “slaves,” and “enslaved,” or just “enslaved,” in its articles.

Language is important.

As noted in the Race Forward report, its ‘Drop the I Word” campaign directly confronted the use of the term “illegal” to refer to out-of-status immigrants in media coverage, culminating in the Associated Press dropping the word from its style guide.

In somewhat poetic fashion, the Associated Press changed its writing style on Juneteenth in 2020 to capitalize the “b” in Black when referring to people in a racial, ethnic, or cultural context.

The Associated Press hasn’t dropped the other “I” word, “inmate from its style guide and has yet to put a stake on the ground between slaves/enslaved.

Some advocates in the criminal justice space stress using person-first language instead of using language such as “inmate,” “felon,” or “convict,” which defines human beings by their crimes or punishments.

For example, The Marshall Project has swapped these words with “incarcerated people,” “people in prison,” or “Jane Doe was convicted of a felony.”

Similar requests have been made from researchers of slavery and advocates for reparations.

As such, I analyzed what kind of language the New York Times used when covering this issue and found that most articles used “slave,” or “enslaved,” interchangeably, or just used “enslaved.”

Often, the word “slaves” would appear in either guest op-eds or quotes from outside sources, with “enslaved” being the prominent choice by reporters themselves.

Personally, I try to say “enslaved people,” but sometimes slip up. I wrote a piece earlier in the year urging folks to start using the term Trans-Atlantic People Trade instead of Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

The words we use are essential in deconstructing commonly held beliefs and reframing how people think about an issue.

I hope that in 2022, more outlets, including the New York Times, start swapping out “slaves” for “enslaved.”

Conclusion

If you read up to this point, then you’ll see that I sprinkled some recommendations throughout the analysis instead of having a separate and distinct recommendations section, so I’m just going to rattle off a few more here:

For reporters, go deeper and do better. The topic of reparations undergirds every other racial justice issue. Include it and the current federal policies, namely H.R. 40, to bring us closer to a racially just society.

If you are in a communications role, connect reparations and other racial and economic justice issues for reporters when you are pitching them.

Black people must control the narrative on reparations, and Black-led news outlets should be the leading voices on this matter. So, funders, fund those organizations!

The media plays a vital role in shaping how a movement progresses and has been used strategically by Black organizers searching for racial justice. For example, Mamie Till-Mobley knew the profound effect of having a Jet Magazine reporter feature the brutalized body of her son on their front page; “let the people see what they did to my boy,” she said.

According to the Washington Post, the image of a young Black man being attacked by a German Shepherd in downtown Birmingham “struck the lightning in the American mind” and made President Kennedy sick.

The 1619 Project and The Case for Reparations are now two staples of Black-American literature that garnered the respective architects MacArthur Genius Awards and sparked a national conversation on race, slavery, and reparations.

Malcolm X said that the media was the most powerful entity on Earth.

How, then, will we use it in 2022 to get closer to our goal of reparations for Black Americans?